Face to Face with Pete Wood

)

Followers of our social media pages will have spotted some fascinating archive images from the pioneer days of motoring. These have come from motoring historian and researcher Pete Wood – and we asked the former Army engineer, classic car journalist and design & technology teacher to tell us more about his passion for all-things classic motoring, why he loves delving into the archives for car owners and how he digs out the nuggets of a car’s history. The story is as fascinating as those archive images – and in next week’s feature he gives some invaluable hints for those looking to research their own Brighton car’s history.

A veteran enthusiast from childhood

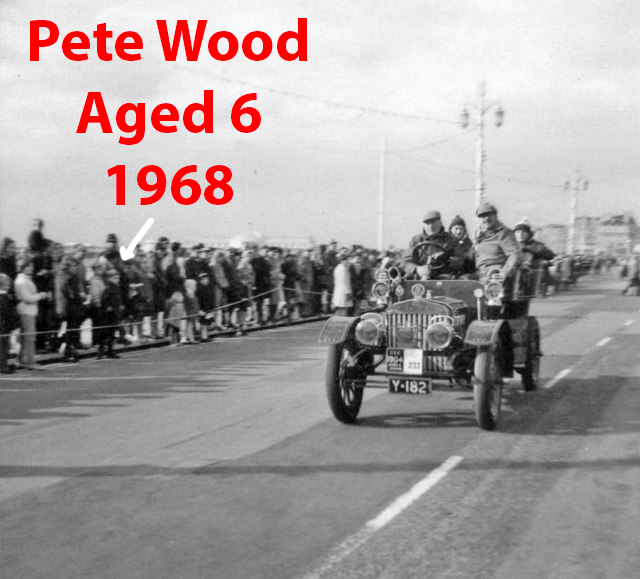

My love of veteran and vintage cars started, as it did for many, with the film Genevieve. I was five years old when I watched it on my next door neighbour’s television - the first colour TV to arrive in our street - in 1967. I’d never seen a veteran car before, but begged my parents to take me somewhere to see them ‘in the flesh.’ They took me to Beaulieu and I still recall how excited I was after seeing, smelling and touching everything that museum had to offer. I couldn’t get enough. My family swapped walks in forests for days spent at classic car shows. I watched my first London to Brighton run in 1968 and literally screamed with delight when a Darracq pulled over into the layby where my family was standing and the lovely owner allowed me to hold his spanners while he worked at fixing the car.

First car – at age 11

On my 11th Birthday, in 1973, my parents told me to look in the garage for my present. Inside I found the rusty remains of an early Morris 8. I knew it wasn’t a Brighton car, but to me it was still pretty special. It was missing parts and I was determined to help find them.

In those days, in rural Kent, there were a lot of abandoned cars in woods and building yards. On weekends I would cycle for miles, stopping complete strangers and asking if they knew where there were any old cars. I soon found a farm that had two abandoned Morris 8s, knocked on the door and asked the bemused owner if I could have a cylinder head. This kindly farmer let me use his tools and even gave me a workshop manual. In exchange I got to clean out his cow shed and he introduced me to the local garage proprietor who gave me a Saturday job pumping petrol.

First job – in a garage of course!

It was a dream come true. I was chatty and, whenever a classic car came in I would proudly tell the owner that I owned a Morris 8. Sometimes in those care-free innocent days, an owner would take me for a spin and soon I knew the location of every classic car in a five-mile radius. I was truly hooked. I learned to drive, aged 13, on an abandoned WW2 airfield in Kent – with wooden blocks screwed to the pedals so I could reach them.

By now I was assisting the garage owner with servicing, while waiting for the next customer who wanted £1 worth of 5-star petrol. You never knew what would come through the door – outboard marine engines, motorbikes, a hum-drum Ford Anglia, or an oil change for a vintage Bentley. Soon I was also working for the affluent and eccentric owner of that Bentley, cutting his extensive lawns on a ride-on mower and hurtling along country lanes in his fabulous collection of cars which included a Bugatti Brescia.

Engineering and historic motorsport in the Army

No one was surprised when, at the age of 15, I announced that I had been to the Army Recruiting Centre and passed the aptitude tests to get an apprenticeship in the Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers where I would be maintaining helicopters. All I needed was my parents to sign the forms as I was underage. A week after my exams, my Mum waved me off at the local railway station and I was on my way, rarely to return home ever again.

My first posting was to Salisbury Plain and I learned of an officer called Major ‘Lord’ Fred Boothby who raced a pre-war MG (and still does). I sought him out and he took me under his wing and introduced me to the rest of the Army’s Historic Race Car Team, including the recently retired Brigadier Hamish MacNinch – and I was now one of their mechanics. Every time one of the team got posted, the others would somehow all land up nearby.

My posting orders were also wangled to ensure I was in a local camp. But it meant that I had to adapt to fixing tanks, or Land Rovers, bulldozers and more. But I was a soldier first and a tradesman second, in the army’s eyes. I was involved in every conflict in which the army was involved. But it never got in the way of me seeking out classic cars. I found an Austin 7 in the Falklands in 1982 and watched, in horror, as an officer outbid me and the oldest car on the island went to a new home back in the UK. Following the Lebanon invasion, I found the remains of a De Dion and came away with the transmission, which I swapped for other parts. By now I had a small fleet of Austin 7s and, each time I was posted, would ‘borrow’ an army lorry to move my collection from base to base (where there was never a shortage of sheds in which to house them, thanks to my officer pals). I spent two years in Northern Ireland and even had my own private workshop in the Maze prison, helping rebuild a racing MGB and Jaguar XK120.

In the First Gulf War of 1991, in the middle of the desert, I found a hastily abandoned WW2 Dodge truck and a Bofors gun. The retreating Iraqi soldiers had poured sand into the engine, to disable it and also jammed the gun. My CO wanted both as souvenirs, which would become ‘Gate Guardians’ at our base in the UK. “Can you fix them, Sgt Wood – and more importantly, get them back to Saudi so we can put them on a ship back to the UK….?” The challenge was on. I hitched both vehicles onto our recovery vehicles and, whenever I got the opportunity, gradually got both working. Soon the Dodge was running under its own power and towing the anti-aircraft gun. I enlisted the help of the army Padre who sat next to me for the whole journey through Iraq, Kuwait and back to the Saudi port. No one argues with a Padre, and I had no problems getting fuel and oil for these ‘souvenirs.’

A war reporter leads me into classic car journalism

Kate Adie, the BBC news war reporter, got to hear about my exploits and promised to assist me in potentially getting a job as a classic car motoring journalist back in the UK. Two weeks after getting back to the UK, thanks to my new contacts I landed a work experience role at Coys. At last I was working on veteran and vintage cars on a daily basis. There I met the Editorial Director of Haymarket Publishing who had received the letter from Ms Adey about a ‘Mad dog soldier who was heavily into classic cars…’

The car history research bug bites

A couple of months later and I was the new Editorial Assistant on various classic car magazines. I was now working with all my editorial heroes – and I was keen to learn. They taught me the value of research, and how knowing the history of a car could increase both its interest and value. Part of my job was to read any newly-published classic car related books and give the magazine’s readers a brief synopsis.

I was given a copy of Philip Riden’s How to Trace The History of Your Car – a small paperback which opened my eyes about the wealth of information hidden in archives and libraries all over the UK. On the weekends I scoured registers to trace the history of my own cars and, as the word got out, to find out the owners of cars belonging to friends. This was in the early 1990s, and digitisation was still in its infancy. I was tracing the families of previous owners the old school way, by going through old phone books held in the reference section of local libraries. But I was yielding results simply with a few calls and then actually visiting previous owners (or their surviving relatives) and drinking endless cups of tea and poring over their family photo albums.

I found that one of my own Austin 7s had a famous first owner – Clarice Cliff, one of Stoke-on-Trent’s finest potters and Art Deco decorators. In the late 1980s (picture below, with me standing) got to meet the elderly ‘Cliff Girls’, ladies who had decorated Bizarre Ware in the 1920s and 1930s and been passengers in my Cabriolet and who all had fabulous and sharp memories - and who all remembered the car! It was a sheer delight to take them out for a spin and learn “Your seats are the wrong colour.” This only happened because of the Ridden book, which taught me how to read a registration plate and work out where the car was originally registered when new. I quickly learned that, in most cases, these cars never strayed far from where they were bought and registered (especially when new). Now, of course, because of the internet and online auctions, cars often travel further afield. But staying local to where a car was first registered usually yields most of the car’s early history.

As I got more experienced, and especially if the car was a bit ‘special’, I soon realised that the local press would often include a reference to the car, its owner and sometimes even publish a photo. Local historians would later also publish these photos in books on local communities and I became a dab hand at flicking through old dusty reference books and charming the, then, often elderly but hugely knowledgeable archivists.

Genealogy expands the search

While I soon learned the value of factory records, archives and libraries, the best results came from tracing the families of the original owners (who were obviously mostly dead). By now I was a design & technology teacher and had met my American wife. She was passionate about genealogy and taught me how to make a family tree. She was expert at working out who had children, and their names. The problem was locating them. But, with the introduction of the publishing of historic electoral registers, it didn’t take me long to work out how to connect with the ancestors of early car owners – either by reaching out to fellow genealogists (who put their family tree on websites such as Ancestry and FindMyPast etc) or by working out where the family lived (even if it was decades ago). In the early days of researching cars, I would just knock on doors, find a street’s oldest resident and simply pump them for information. “Oh yes, the Smith family moved about 20 years ago. I think I have their new telephone number somewhere. Let me go and check. Here it is…”

I finally acquire – and research the history of - my own veteran car …

On the day of our wedding, one of the vows my new bride had agreed to was “To attend every London to Brighton Run as a spectator.” I never thought I would actually own a veteran car; too expensive. After five years of waving the entrants by, while stood at one of the hills in Sussex, my wife said, “If we ever DO buy one of these cars, it MUST be a Cadillac.”

That same day, I joined the Early Cadillac Group and set about trying to find a car within my budget. I struck lucky almost immediately. But the car was in a very bad state and would take 7 years to restore. It was from 1903, the first year of production car. It needed total restoration. We emptied the family coffers and the car was delivered. My students helped me strip it down and I sent the chassis to be shot blasted. There, some initials were revealed below the layers of old paint, oil and grease – ‘BT4’ and ‘JVK.’

None of this made any sense to me, or the early Cadillac experts. BT4 was, however, possibly an early Yorkshire registration. But the car had come from America, so again did not tally. But I had no history of the car whatsoever, and needed to follow every lead. So I wrote to the archivist in East Yorkshire. A month later, she called me to say, “We have a photo of a Cadillac with that registration number – BT4. It came from a local historian called Mike Wilson. He lives in Bridlington.”

I Googled Mike and found he had a website – and, there was another photo of a 1903 Cadillac with the registration BT4. Mike thought the owner was a wealthy landowner. The name did not match the initials, JVK, stamped into the chassis however. Was BT4 just a coincidence? In my experience of researching hundreds of classic cars, every clue is vital. I used a website called FreeBMD which lists (free of charge) almost every single person’s place of birth and the approximate date, marriage and death from the 1840s onwards. The beauty of this site is it allows you to use ‘wildcards’ so if you are not sure of the spelling, you can just put in the details you are sure about and put an asterix. I got hundreds of ‘hits’ from J*V*K* but when I narrowed it down to Bridlington, which Mike Wilson had identified in the photos of BT4, it came back with only John Vere Kinsley who died in 1906.

I rang Mike and, once he had got over the initial shock, said, “My Great Aunt was the maid for the Kinsley family. The photos of the Cadillac are from my aunt’s photo album. She worked for them for 20 years and she was a benefactor of John Vere Kinsley’s will. I still have a copy in the attic, in a trunk.” The will showed that Cadillac BT4 was sold on his death and even named the buyer. I now had another clue – and the family name was unusual, which made it a lot easier to investigate. Mike kindly gave me the original photos, in exchange for some high-quality digital copies. I found the descendants for the second owner in under five minutes and, on the same day I made contact with Mike, I called the grandson of owner two. Yes he had a photo album and some other memorabilia. But he was going on holiday and I would have to wait. Two months later, I got the famous call. Not only did he have a photo of the Cadillac, but he also had his grandfather’s diary and the Cadillac was used to carry bicycles at his repair business in London. He also had the buff logbook for the car! I asked for a copy but, just like Mike, the family were only too happy to let me have the original – plus the previous owner’s driving licence from 1906. All they wanted was the chance to have a drive in the car when it was restored. Deal!

The Early Cadillac Group were able to tell me who the car belonged to in the 1960s and ‘70s. I made contact with the relatives and, as excitedly announced on the Single Cylinder Cadillac Facebook Group, the original brass lamps had been located in a barn in Middle America. Fantastic! Little by little, I was able to piece together the middle part of the car’s history, using the memories of the descendants and also via newspapers (for which I have a subscription to see digitally scanned media from libraries all over the world). I worked out that an American Serviceman, serving in London in WW2, had bought BT4 and shipped it back to the USA. He had sold it to a millionaire car collector who had his own steam train railway line on his property and ferried friends and customers in the Cadillac. In just a few months, and with a lot of luck, I had the complete history of BT4 from Day 1, as well as original paperwork all of which I proudly presented to the VCC to gain the car’s passport and reclaim the original registration. The day the V5 arrived, in the post, was emotional to say the least.

On 21 August this newbie veteran car driver took to the roads of London in BT4 and in November I will drive it on the RM Sotheby’s London to Brighton Veteran Car Run for the first time – and I can’t wait!

Retirement from teaching means more time for research!

Since I retired from teaching I have been able to dedicate even more time to researching the history of cars for their owners. I work on a results only basis, and don't charge a penny if I come up with zero results. For me, it's all about the chase, and makes my retirement more fun.

I also do not charge an hourly rate. Instead, I say “If you're happy, pay me what you think I deserve.” I have rarely been disappointed with this approach (though once, after working for four days solid and travelling to an archive 300 miles away, the client sent me just £10. Sigh).

Having the complete history of your car can and will significantly increase the value of a car (by around 25%), especially a veteran or vintage car. I once worked out the complete history of a very rare vintage sports car, having started with just the name of the previous owner, and an auctioneer revalued this car as being worth an extra £200,000 as a result). The owner gave me a very handsome ‘tip’ as a result of this…

Next week Pete will give you invaluable hints and tips for researching the history of your own motor car.

Contact Pete

If you’d like to talk to Pete about researching the history of your Brighton car, you can email him here.

Pete runs the newly-established Facebook group ‘The London to Brighton Veteran Car Run’ and is also an admin on the Single Cylinder Cadillacs Group on Facebook.

.resize-500x189.png)